Greetings folks, and today on LGR I am proud to present the fabled AdLib Gold 1000 Stereo Sound Adapter. An IBM PC-compatible sound card which, after multiple delays, launched at a suggested price of $299 in the US sometime in late 1992. More or less, its release is a bit complicated but we’ll get to that. For now lemme just go ahead and say how much I’m freak in’ out with excitement recording this footage. Cuz dude, seeing an AdLib Gold in person, still in the box, unused?

Among retro PC enthusiasts, that’s like finding a golden unicorn that craps diamonds, it’s just not a thing. Yet here it is, looking’ spiffy!

And it’s all thanks to Trixter, aka Jim Leonard of The Old-school PC, Check out his YouTube channel if you’re into this kind of thing too, the man’s a fountain of knowledge and some of the items in his collection are literally one of a kind.

Not the least of which being this pristine AdLib Gold 1000, a card that I’ve been wondering about ever since I was eight years old looking at this sound card listing in the setup program for SimCity 2000 for DOS. And as an adult, I’ve been trying to get one for over a decade now with zero luck.

I’ve bid on just about every one that’s shown up online, but ah. Well just look at these prices and you’ll see what’s been stopping me. AdLib Gold’s rarely show up for sale at all, and when they do, the lowest price is rarely less than a thousand bucks for a loose card.

With more complete examples going for between two and four thousand dollars, or even more. And these are sold auctions, not Buy It Now prices sellers came up with outta nowhere. So seeing as this has become one of the most valuable expansion cards around?

My goal with this video is to see whether or not the AdLib Gold lives up to its legendary performs on early 90s PC hardware. And of course, play some Dune, because that’s just the law when it comes to the AdLib Gold. And man does this thing sound nice.

But so did plenty of other sound cards in 1992, and most of those can still be had for a fraction of the price of an AdLib Gold. Heck, it’s not even Sound Blaster compatible, meaning that unless the game specifically supports the Gold, or you try a workaround through software, then chances are it won’t play sound samples at all. So what’s going on, what makes the AdLib Gold special?

Well, let’s see if we can figure it out by unboxing this thing and taking a closer look at what’s inside. So, first up inside this edition of the Gold we’ve got an assortment of paperwork, including a license agreement, a note on experimental Sound Blaster compatibility through the use of a TSR, and a folded sheet going over the details of the included Windows 3.1 drivers and software.

Which is stored on these four 3.5-inch diskettes, containing all the programs for DOS and Windows. Then there’s the instruction manual, with 101 pages going over the setup and operation of the card as expected, but most of the book is dedicated to explaining the multiple additional programs it comes with and using its convoluted selection of drivers.

Finally, there’s the actual AdLib Gold 1000 card, which has remained sealed and unused for nearly 30 years. Until now, holy crap. And yes, Jim gave me permission to do this, so while I’m no doubt committing a sin at least I’m doing so with the lord’s permission.

Yeah that right there is as fresh an AdLib Gold as you’ll ever see. The last time this was touched by human hands the first Mortal Combat had just hit the arcades, End of the Road by Boyz II Men topped the Billboard Hot 100, and Disney’s Aladdin was about to release in movie theaters. And I wish I could let y’all take a whiff, it smells fantastic.

Ah. Smells like an early 90s pallet of electronics and broken dreams. The last thing in here is a CD audio cable, a bit of a weird one with the typical MPC connector on one end but connecting to the card using the kind of 4-pin molex connector that 3.5” floppy drives use for power.

And yeah, that right there is the complete boxed contents of an AdLib Gold 1000 from late 1992. Beautiful, just beautiful. As is the card itself, with its hundreds of little components and fascinating chips tidily laid out in a grid on that golden brown PCB. It even sparkles somewhat, adding to the golden nature of the Gold.

There are also these intriguing headers that allowed for multiple add-ons and upgrades. With these two accepting the so-called Surround Sound Module, a daughterboard sold separately for $89. Really it seems to be more of a two channel DSP adding reverb, chorus, and delay, and applied a kind of “virtual surround” effect in stereo. Unfortunately I don’t have one to show as they’re even more rare than the AdLib Gold is. There was also a prototype clone made by a user on Vogons, but it seems that up to this point it’s never been publicly made available.

Then there’s this header to the left of that which added the SCSI Module, sometimes called the CD-ROM Option. I haven’t found any photos of it, and I’m not even sure it was ever released. Same with this header here, which would’ve taken the PC Telephone Module. Again, can’t find any pics and I don’t think it ever made it to production, despite being touted in Ad-lib’s marketing.

It’s also completely left out of this later edition of the manual, saying the connector is “not currently used,” along with the two-pin header beside that which was meant to connect your motherboard’s PC speaker output. You’ll also note the 1991 copyright printed on here, implying that it was released that year, but nope!

Taking a look at the components reveals date codes of 1992, with most being mid-September, and the earliest reports of sales I’ve found dating to that October. A 1991 launch might’ve been the original plan at Quebec-based AdLib Incorporated, but there ended up being a real struggle around getting the AdLib Gold on store shelves.

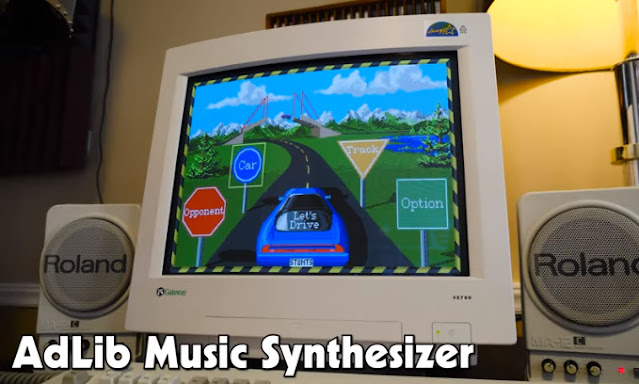

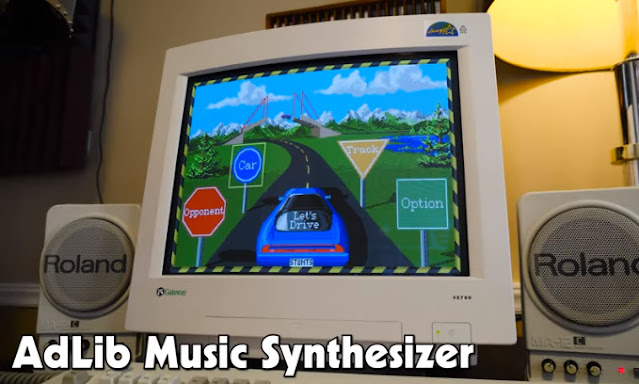

Yeah it’s a bit of a thing, so before we install the card into a PC, let’s get comfy, grab a tasty beverage, and dive into the story behind this old beast and how it almost didn’t get released at all. Our story begins with how the AdLib Gold came to exist in the first place, which goes back to 1987 and its predecessor: the AdLib Music Synthesizer, a card which really kicked off the whole PC sound card space. There were sound options before it of course, but healthy support from software developers meant the AdLib soon became the defector standard. A gold standard, if you will. It made your games go from sounding like this: to sounding like this!

Fantastic stuff in the late 1980s. But it used off the shelf parts and pre-built Yamaha chips, so it was easy to clone and improve upon. And companies like Creative Labs jumped on it with cards like the Sound Blaster in 1989. It was competitively priced and packed the same YM3812 OPL2 synth as the AdLib, providing perfect AdLib compatibility. Its other killer features were a DSP providing 8-bit PCM sample playback in mono, along with recording inputs and a 15-pin joystick port doubling as a MIDI interface, freeing up several expansion slots.

Making the poor little AdLib immediately obsolete. And AdLib wasn’t having it. Work began in 1990 on what would become the AdLib Gold, with news of the follow-up breaking at the Spring Comdex show in May of 1991. It was out for Sound Blaster blood with Yamaha’s new YMF262 OPL3 synth, 44.1kHz PCM sampling in stereo, a joystick and MIDI interface, and compliance with the new Multimedia PC Standard. And also at Comdex that spring?

The Creative Labs Sound Blaster Pro, with MPC Standard compliance, 22kHz mono PCM sound, and dual Yamaha OPL2 chips instead of an OPL3. AdLib clearly had better specs with the Gold so that’s that, AdLib wins right?

Thing is, while AdLib had sold nearly a hundred thousand cards, Creative Labs were already counting their customers in the millions. They also had the marketing, the distribution, and rapidly increasing software support, and they weren’t afraid to throw their weight around with suppliers. Suppliers like Yamaha.

So when AdLib showed up with fancy OPL3 chips, all Creative had to do was be like, “hey lemme in on that.” And thus we got the Sound Blaster Pro 2 just a handful of months after the Pro 1, packing the same OPL3 chip as the upcoming AdLib Gold. But AdLib still had the upper hand on sound quality, with 44kHz stereo output, filters for double over- and under sampling, and a 12-bit DAC accepting 8, 12, and 16-bit PCM samples.

Great stuff, but a lot of it relied on Yamaha’s new chips that weren’t yet finalized. Then came Ad-lib’s money problems. Developing a cutting edge sound card wasn’t cheap, with research and development costs reportedly going over budget fast. And AdLib relied on both venture capital funding as well as loans from the Canadian government to keep the company afloat. But they’d be able to pay it all back once the Gold came out, right?

Problem was that Yamaha supposedly told AdLib the new chips were buggy and needed more testing before production. Though depending on who you ask, that may not be the full story. Rich Heimlich, author of Sound Blaster: The Official Book, has alleged it was Creative Labs who pressured Yamaha into delaying the chips. And it only had to be long enough to finish the Sound Blaster 16 and beat the AdLib Gold to the market. What poor AdLib doesn’t understand, not being a technology company. They’re buying, as I mentioned, off the shelf parts from Yamaha.

They had this chip known as the MMA chip, it was a critical chip for the production of this card. Yamaha continued to have problems bringing it to market, to get it to pass testing. And I thought this was all just good luck for Creative. Then I had a call one day with Sims and he made it clear that “this chip will pass when I say it passes.” And I had to sit back for a moment and go “whoa, that’s heavy.

This guy is controlling Ad-lib’s fate.” So month after month, Yamaha reportedly told AdLib that the chips were flawed and delayed. Launch dates went from fall of ‘91 to winter, then to March of 1992, then April. Understandably frustrating potential customers, who wondered if the Gold would end up being vaporware.

Finally, it all came to a head on May 1, 1992, after their government loan fell apart and VC funding was pulled. Leading to AdLib Incorporated declaring bankruptcy and immediately shutting down. Apparently without warning, with employees going into work normally that morning and being escorted outside unemployed by the afternoon. And guess what launched a month later?

The Creative Sound Blaster 16, complete with all the bug-free Yamaha chips they needed. As for the AdLib Gold, obviously it came out eventually. But the company shut down before they could sell them, with the only cards up to then being prototypes and pre-release review units. From what I gather though, a number of retail units were manufactured before they shut down, but they were left hanging out in a warehouse somewhere after the bankruptcy. There was talk of Creative Labs maybe swooping in to claim the spoils of war and buy up what was left of AdLib, but that never happened. Instead, AdLib Inc was sold to a German holdings company, Binnenalster GmbH, over the summer of ‘92.

The few manufactured Gold cards were sent to distributors as-is, followed by the company being renamed to AdLib Multimedia, and a second run of AdLib Gold 1000s were packaged up and sold with the new branding. Like the Gold we have here, which has the post-bankruptcy AdLib Multimedia name on the box and documentation.

But even after years of waiting for a new AdLib card, the Gold simply didn’t sell. By then the Sound Blaster 16 was out, and the Pro Audio Spectrum 16, the Logitech Soundman, the Turtle Beach Multisound and so on. If the Gold 1000 had actually released in 1991, or even the beginning of ‘92, it could’ve claimed a decent slice of the pie. But by late ‘92, early ‘93?

The Gold 1000 had arrived too late to its own party, and without real Sound Blaster compatibility, it was dead in the water. Computer Gaming World magazine straight up asked, why bother with the AdLib Gold at all?

They couldn’t think of a reason to get one considering the competition. The Sound Blaster 16 was $50 cheaper than the Gold and the Pro was a hundred dollars less, both of which had better games support than the Gold. So yeah, that $300 sticker price didn’t last long. The cards were selling for less than a hundred bucks by January of 1994, and by March some people were reporting clearance prices as low as $20. Ouch.

No surprise then that support didn’t last long for the Gold, and the company was sold yet again to Soft world in Taiwan. They used the AdLib name for a while to sell their own cards and peripherals, including sound cards of course, but also some VGA graphics cards, and even dial-up modems with AdLib branding before fading into obscurity. And the planned AdLib Gold 2000 and Gold MC2000 Micro channel cards never got released from what I can tell, despite several articles and ads mentioning them back then.

The Gold 2000 was supposed to have SCSI on-board with an interface built into the card, according to the original manual. But all mention of this was removed later on, with only the SCSI module headers remaining. But enough about Ad-lib’s untimely demise. Instead, I’d rather celebrate their final achievement by soaking in the Gold 1000 experience. So let’s jump into that by yanking out the Sound Blaster Pro 2.0 from the LGR Wood grain PC, and slot the Gold card down in its place.

Pretending, if only for a moment, that it’s 1992 again and we’re installing a new sound card for the first time. And we kind of are, since this particular card has never been installed in anything, much less powered on since testing at the factory. Right, so I’ve already removed the old startup file settings, making our first order of business to install the AdLib software from our trio of floppies. I know there are four of them, but the blue one seems to be redundant since everything’s already on the first three. After it’s finished you get this amusingly-worded message claiming that “the AdLib Gold is a sophisticated product and uses a lot of system resources.” Yeah that’s one way to put it, y’all keep this message in mind.

Thankfully no software’s loaded on startup, just a couple lines added to autoexec that sets the install directory and the I/O address jumpered on the card. All the IRQ and DMA settings are conveniently controlled through software something we can test in the AdLib Gold Test Program. This lets you select up to ten tests to test out testingly one test after another, including some for the optional modules and 15-pin MIDI adapter. ”Get ready for sound so rich, it has to be called gold!”

Aha, “rich” sound, gold, nyeheh. Anyway hey, it works!

That’s a relief. So let’s try out the bundled software, beginning with the Mixer Panel: a TSR you can load up to adjust the card’s volume settings and playback options. Once this is in memory you press ALT+SHIFT+M to pop it up wherever you happen to be in

DOS, letting you change input and output levels and tweak the Surround Module should you be lucky enough to have one. I don’t, but check out those DSP options.

It’s a decent spread of reverb and delay effects that soon became the norm on wavetable and General MIDI modules in the mid-90s. Even without the module there are a couple of special output modes, referred to as Pseudo and Spatial. The manual describes these as forcing stereo separation and imitating surround effects, and to me it sounds like a light phase shifter. And all this would’ve been awesome to mess with in ‘92, but I’ve got a couple complaints. For one thing, your volume and EQ preferences are often overwritten to the levels used in games running in AdLib Gold mode.

And since some of those games don’t have built-in mixing options, I ended up having to use an external amp to adjust the volume myself so that it didn’t clip like crazy through my speakers and recording devices. My other issue is that anytime the Mixer Panel is loaded in the background?

You give up a ridiculous amount of conventional memory, taking this rig down to a paltry 475K. What the heck?!

And it gets even worse if you load the standard AdLib. Gold driver bundle, which drops you down to an unreasonable 398 kilobytes of free conventional memory. Brutal. Fortunately these drivers aren’t required for gaming, but still. That setup warning about memory wasn’t kidding’ around. “sophisticated product.” Yeah that’s one way to say your drivers are bloated beyond belief.

Ah well, at least with the drivers loaded we can enjoy Juke Box Gold, the successor to Ad-lib’s classic Juke Box. Even if it’s really underwhelming to look at, designed more like a file manager than a music player. The old CGA Juke Box was way better than this, what happened?!

I guess they were a little preoccupied getting shafted by Creative and juggling multimillion dollar loans, but still, my disappointment is palpable. At least the demo songs are absolute bangers. bangin’ AdLib Gold tunes play for a while Oh yeah, that’s the good stuff right there. Each tune makes solid use of the YMF262 OPL3 synth, but it also drops a nice buncha samples in there for digital percussion and any sounds that aren’t easily reproduced by FM synthesis.

The first being Voice Pad, which is a sticky note/alarm clock/reminder app that uses the microphone in to let you record voice messages to be reminded about at a later date.

-Greetings, this is an AdLib Gold. And Creative Labs can suck it.”

-”Greetings, this is an AdLib Gold. And Creative Labs can suck it!”

-Daily alarm. The other bundled thing is the Soundtrack Synchronization Editor.

Which lets you combine Juke Box songs, PCM sound samples, and image files together to create audiovisual presentations. So yeah, a slideshow with music and sound. Unfortunately I wasn’t able to get the visual side working, so all it does is play cued up music and sound.

”Ad-lib’s new 22-voice music system!” Now as for the Windows 3.1 side of things, the Gold only came with a handful of drivers and setup files, which sets things up to work largely the same as any other MPC-compatible sound card with an FM synth and PCM sound in Windows. You get some MIDI Mapper configs, a generic OPL3 synth setup panel, and that’s it. No Windows versions of any of the AdLib software, no Windows mixer, no Windows Juke Box. Eh. Under Windows, the Gold becomes a no frills generic Yamaha-based sound card.

All right, it’s high time we try a few DOS games! And considering my own childhood experience, the first one I’ve gotta test is SimCity 2000, since it’s the first time I can remember learning of the card’s existence. and would ya look at that?

Seeing “AdLib Gold detected successfully” 26ish years later is downright surreal. Let’s hear what it sounds like!

SimCity 2000 music and sound effects Well. It sounds pretty much the same as my Sound Blaster Pro 2 did in here, for the most part. They’re both using the same exact OPL3 FM synth for music so it’s not shocking that’s nearly indistinguishable. Where it does differ is with some of the sound effects, and not in a good way.

On the Gold, they play back at entirely the wrong speed. It’s not like this with every sound, only some of them, but they’re higher-pitched than they should be. From what I gather it’s because the Gold only plays sound samples at a few preset frequencies, and any sounds recorded at rates in between those end up playing at the wrong speed. So that sucks!

But even when sounds aren’t on chipmunk mode, most games with quote unquote “AdLib Gold support” mostly treat it the same as a Sound Blaster. So you get the FM synth and digital effects playing back as expected and that’s that.

However, the light sprinkling of titles that really take advantage of the Gold fare much better. With Dune by Cryo Interactive here being the go-to game to try for intentional support for the AdLib Gold. Yeah when music is written with the Gold’s capabilities in mind it sounds lovely, even without any effects supplied by the optional surround module. As a point of comparison, here’s a direct recording of the Gold side by side with the Sound Blaster 16.

Now, this is only one comparison of course, but to my eardrums the AdLib Gold sounds warmer and more complete, with bass and midtones that are ample without muddying up the composition, and notably wider stereo separation, especially with headphones. Whereas the Sound Blaster comes across as dry and somewhat harsh. It certainly sounds sharper and more bright, but in a way that I’d describe as “raw” as opposed to “crispy.”

The difference would be much more notable if I had a surround sound module with all its fancy reverb and delay effects going, but yeah, even without it I think the Gold sounds great. Some of this is down to the unique composition of Dune’s soundtrack, but every other game I’ve tried gives similarly pleasing results.

No doubt due to the overall quality components being used on-board and some of those Yamaha chips, like the YAC512 DAC and the YMZ263-F. Also known as the MMA, the main chip that apparently held up the AdLib Gold’s release date for so long. Whether or not the quality improvement was worth the trouble, well, that’s debatable. But the difference is clear regardless. And even more apparent is the difference between noise levels.

Older Sound Blasters are notorious for their noisy output, and AdLib chose superior components across the board to reduce that. Back to the games though, because while Dune understandably takes the spotlight, another nice example of the Gold Standard in action is Cryo’s KGB. No surprise really since it shares the same composer and HERAD Music System as Dune. Dang that sounds good. But unfortunately, Cryo Interactive was one of the few companies to fully follow through on supporting the Gold. Despite Ad-lib’s hope that most would hop onto their alternative to the Sound Blaster standard, the so-called “Gold Standard.”

Instead, most games simply treat the Gold like a generic Sound Blaster clone. Speaking of which, the AdLib Gold makes a terrible Sound Blaster clone. Not that it was ever meant to be one since AdLib intended for it to be its own thing.

But by the time it finally released, having Sound Blaster compatibility was essential, and the AdLib Gold didn’t have it. Best you could do was half-baked emulation through software like the included GOLD2SB Simulator. Two problems though. One, it was never finished, so support is minimal and I haven’t had much luck with it. Nearly every time it ends up crashing with varying types of unexpected exceptions. And even then, it’s a clunky TSR that takes up enough conventional memory that you immediately run into problems running it with games that need more.

At this point I’d rather go back to a noisy Sound Blaster than waste time juggling bytes trying to get emulation working on a game by game basis. And well, that kind of caps off the AdLib Gold experience. Is it worth its weight in gold?

Like, between two and four thousand dollars’ worth?

Of course not, are you kidding me?!

Do I still wish that I had one though, ohh-ho-ho you bet I do. It’s an absolute legend of a sound card, and being able to use one at all is dopamine-spiking levels of special. Yet the fact remains that its use cases are minimal and games support so lacking that I can’t help but come away a little disappointed. It’s very much one of those “don’t meet your heroes” situations, especially without the surround module installed. It’s got some fantastic filtering and low noise output, which is awesome. But there are only a few titles that play to its strengths, and everything else either treats it as an off-brand Sound Blaster or doesn’t work at all. So why does it end up selling for so much cash?

Well in my view, it’s a combination of scarcity, reputation, and timing. There were very few of them manufactured, even fewer that still survive, and even less than that which still have the box or the surround sound module. Rarity alone doesn’t equal value though, so I think the rest comes down its legendary rep among a certain subset of PC hardware enthusiasts.

Basically doofuses like me who remember seeing it mentioned back in the day, learned about its history and the fight with Creative Labs, and have repeatedly heard of its reputation as one of the best-sounding OPL3 cards ever made. And honestly, there’s just the fact that prices on computer hardware around 25 to 35 years old is inflated in general. Even generic 486 clone PCs are going for between three and five hundred dollars for Pete’s sake.

So a truly rare beast like the AdLib Gold, which captivates the imagination of more collectors than the supply can ever fulfill?

Prices inevitably skyrocketed, and for collectors who now have cash to burn, mythical cards like the AdLib Gold are the cream of the crop. How long that’ll last, who can tell, and I’m sure there’s a bit of a speculation bubble happening at the moment. But for now, the Gold stands as a geeky status symbol. So while it never earned its “Gold Standard” label as a well-supported sound card in the 90s, it’s unquestionably become a gold standard in high-priced PC components decades later. And hey, it sounds pretty good, too. And if you liked this episode on the AdLib Gold,

And as always, thank you for watching!

Comments

Post a Comment